Shipsides and Beggs Projects at the Death Of Delawab 2010

(Slavka Sverakova)

Introductory reflections:

Richard Long (1945), A line made by walking, 1967, copyright The Artist

Pawel Althammer (1967), Path, 2007, Munster, photo Roman Ostojic

Both works imaged here are conceived as becoming unforgettable, their forms kept simple under the dominance of a related narrative. Willingness to challenge convention is included within the concept of the artist - the oscillation between a professional artist and an amateur.

Long presents the photograph of his intervention in nature as a work of art, he makes the mark by walking and then takes a photographic image. He is the participatory agent who presents the experience within the poetics of mimesis. Althammer’s Path was taken by Ostojic as a document of a narrow cut swath for walking.

Long demonstrates how new art comes from old, it is frail and includes its own past, that is the artist’s capacity to re-enact the beginning inherent in birth by actions that bestow significance of an individual’s life. Walking is a supreme skill that increased the capacity to sustain life. An upright moving body allows the eye to see both danger and protection early. This is the existential bind between walking and seeing that Long renews for our attention. In addition, he freezes the action into a two dimensional image paralleling paintings and documentary, as established forms of culture. Another aspect worth noting is the way that Long increases freedom of the individual as an aesthetic value. Walking as a tool to make a mark on a ground is an unexpected choice. It is an action, unpredictable and irreversible, aspiring to belong to drawings. As the traditional trinity of eye + brain + hand replaces hand by feet, the brain also selects the respect for nature as a value. The interference is minimal, only the positions of what is already there are slightly shifted. The eye is almost redundant during the process, presiding fully over the photographic image later, preserving most of the aesthetics of the classical - classicist art: clarity, restraint, completeness coupled perhaps, with a lightness of being with a touch of extraterrestrial eternity.

Althammer grounds his work in the here and now. The Dionysian Althammer, born in the year when Long made that line by walking, relies on the intoxication of the experience a visitor may have participating in his visual prompts. No photograph can approximate that. I watched a video of someone taking a photograph every ten steps – nothing like a walk on that field of wheat. Appreciating it as art conflicts with recognition of the damage to a life supporting crop - and in my case with memories of walking between fields during school holidays. I can recall an aesthetic experience but did not and do not consider it an art experience.

“...it would not necessarily require an artist to make it” wrote Roberta Smith, and added that the whole Munster 2007 exhibition may be thought of as “experimenting with definition of sculpture“.

Althammer applied hubris, an intentional damage to a gift of nature and farmer’s skills. Aristotle defined hubris as causing shame simply for a pleasure of it. After Hesiod (7th century BC) and Aeschylus(5th century BC) used hubris to describe wrong action against divine orders, Aristotle focused on hubris between people “Young men and the rich are hubristic because they think they are better than other people”. Althammer shifts the issue between humanity and nature, between art and nature. He also evokes individual freedom, but this time tarnished by hubris. The Path being almost a kilometre long cannot be seen fully from any one standing point. It frustrates any possible clarity of experience beyond the reduction to a primeval being on a path you do not know the end of.

Both Long and Althammer employ fragments of ordinary behaviour. Althammer secures his as art by display at Munster 2007 event, i.e. by placing it onto a site occupied by art institutions. Long achieves that by photography, drawings, texts, installations and performance, i.e. recognized art practices.

The strategy of placing something outside its context of origin and re-positioning it in art calls not only for performative intervention but also for skills that expand imagination.

That strategy also reverses the system of arts as described by W Morris at the end of 19thC – his “lesser” arts, those that support and sustain life, become the dominant set.

A quick inquiry into analogous art practices brings forth a wealth of evidence. I have in mind not only Land Art (term coined by R. Smithson in 1968 in the US) but also cooking (e.g. Rirkrit Tiravanija, Adva Drori, Pauline Cummins), and the many strands of performance art. Tiravanija re-organized a gallery as a contemporary kitchen that would stimulate unexpected interaction between participants and displace the expected role of art. Adva Drori makes omelettes with slogans written in red pepper asking different questions, including; “Am I an artist?” Early on, Noguchi and Sonfist inextricably linked two principles; the work of art and the site, the landscape, swap identities. Later, Richard Long and Andy Goldsworthy identified natural materials as conditions for a walk, or cut ice to become a work of art.

Noticeable is an inherent connection to sculpture and drawings. Soon however, the lens stepped in as a convenient means of limiting some of the ephemerality of art practice that produced art that is eaten, or otherwise “consumed” at the time of making. These art practices are grounded in the conviction that perception is a kind of participation, in addition they invite physical participation, i.e. eating the food, walking the path etc. Even more demanding is Roden Crater (1974 – 2011, www.rodencrater.com), which offers a multisensory experience. James Turrell has been well prepared for the conundrum of perception, in particular the visual one, by studying psychology first and art later. He focuses on forming space through light, using eyes to penetrate space. He draws attention to the limits of seeing, yet makes seeing the very subject. Recently he added scuba diving and skiing to the means of exploring the double bind of origin and displacement.

Anaximander (610BC – 545/6 BC) pointed out that origin and demise of origin come from the same source. He had in mind existence; I am focusing on praxis – in this case climbing and visual art.

Dan Shipsides and Neal Beggs independently and mutually unaware made their initial gallery climbs just months apart - evidence that ideas not only occur over and over again, but also to several people at almost the same time. In 1997 Shipsides made live climbing performances at Catalyst Arts, Belfast (Under a frogs arse at the bottom of a coalmine). Then as a co-curator of the first Perspective in Belfast, I selected Shipsides’ proposal (The Stone Bridge) during the summer of 1998 to climb the gallery’s walls as a performance and show the video of it for the duration of the exhibition. Later that year Beggs made his climb (Surfaceaction) at Glasgow Project Room and the subsequent video was presented during the exhibition.

"The Glasgow Surfaceaction took place in a show I curated with Kevin Kelly (now living in Dublin, we had both just finished our MA at Glasgow) called Mountain Madness (Dec 1998). It was an artist run show at the Glasgow Project Room. There were about 15 artists in the show and I made my climb around the gallery before any of the other artists moved in to position their work. So when the public came to see the show they saw many works on the wall and floor and between these works lots of scars and holes made by my axes and crampons (the making of the work was not public). The video was presented on a very small tv monitor on the floor of the gallery along with several other videos." (Neal Beggs, email, 12/12/2010)

Significant difference defined the status of climbing in an art institution. Shipsides put forward personal commitment and skills in both activities to the judgment by the viewer simultaneously, Beggs preferred suggestive marks on the wall to have a moment on their own, before the video would give an entry into their origin.

In both cases, the lens-based display scaled down the original action and subtracted the real-life energy into two dimensional memory charged with the task of triggering imaginative attunement. The possible challenge to this concept was muted, the visitors were already used to video as art.

Moreover, the video posits itself between art and a document of art. It is this ambiguity that will prove both a challenge and a solution for the collaborative projects embarked upon by Shipsides and Beggs around 2003, referred on their websites as Shipsides and Beggs Projects.

One more detour: Outside collaborative projects each artist has expanded independent research concerning climbing and visual art.

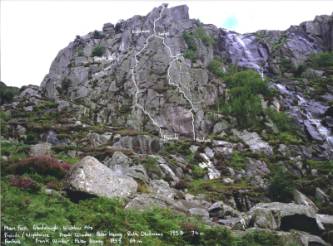

Shipsides for instances superimposes drawing of the climbing done over the photograph of the rock face. It is a record, a virtual map of a climb done or planned – the viewer is not assured which – as a visible mark of a non-visible experience, even of one that did not happen, yet. Plausibly intuitive mimesis embraces the insecurity and the doubt as equals. Moreover, while viewing the drawing the idea of safety and audacity in climbing nudges away the perception of it as beautiful. Happily, the photograph of the mountain, of the landscape has no similar qualms, it harnesses all to switch on the sublime and the beautiful. I have not perceived, what others might, an intrusion of romantic escapism. The fore-grounded demand on skills and rational safety measures, takes care of that.

Capella Head Point. Dan Shipsides. 2008

Shipsides pointed out the similarity between climbing and art in relation to the project (Pioneers 2003) as follows:

…the landscape was literally felt out with their fingertips exploring handholds, finger-cracks and employing particular climbing movements. These details highlight Frank and Elizabeth’s own sense of creativity - that their actions, their minds and bodies were creating or making something new. In that they are created and named, the routes themselves reflect and may exist as “artworks”. They can be read in terms individual style, technique, context and vision and can claim their place in cultural history. Through the sense of exploration and endeavour these climbers’ landscapes echo aspects of the modernist ideal but here they do so with a different poetic, one which is gentle, witty and reflective. It may be topical to compare the “national” mountaineering effort or ethic of the Irish Republic with the more bombastic efforts of older nations during that period. The activity of these climbers offers a “modern” representation of the Irish landscape and provides a contrast with the sense of “native belonging” found in many post-independence visions of Ireland’s natural landscape.

Glendalough (Pioneers) Dan Shipsides 2003

***

The story of collaboration.

Alphabet Climb (2004, left), Ulster Iron Way (2010, at the left banister and the landing), Marmolada Bees (2010, right), installation view at the Death of Delawab. Shipsides and Beggs Projects.

Since becoming aware of each other’s work in 1996 Shipsides and Beggs have been occasional collaborators. In 2009 they decided to firm up their collaboration under the title 'Shipsides and Beggs Projects' to which all the earlier co-authored works and research are now attributed. Past projects include User's End (Be-Part, Belgium), The Hanging (Tulca, Galway) and The Alphabet Climb (Montserrat, Spain).

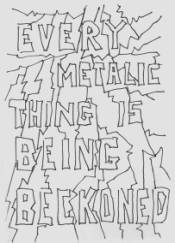

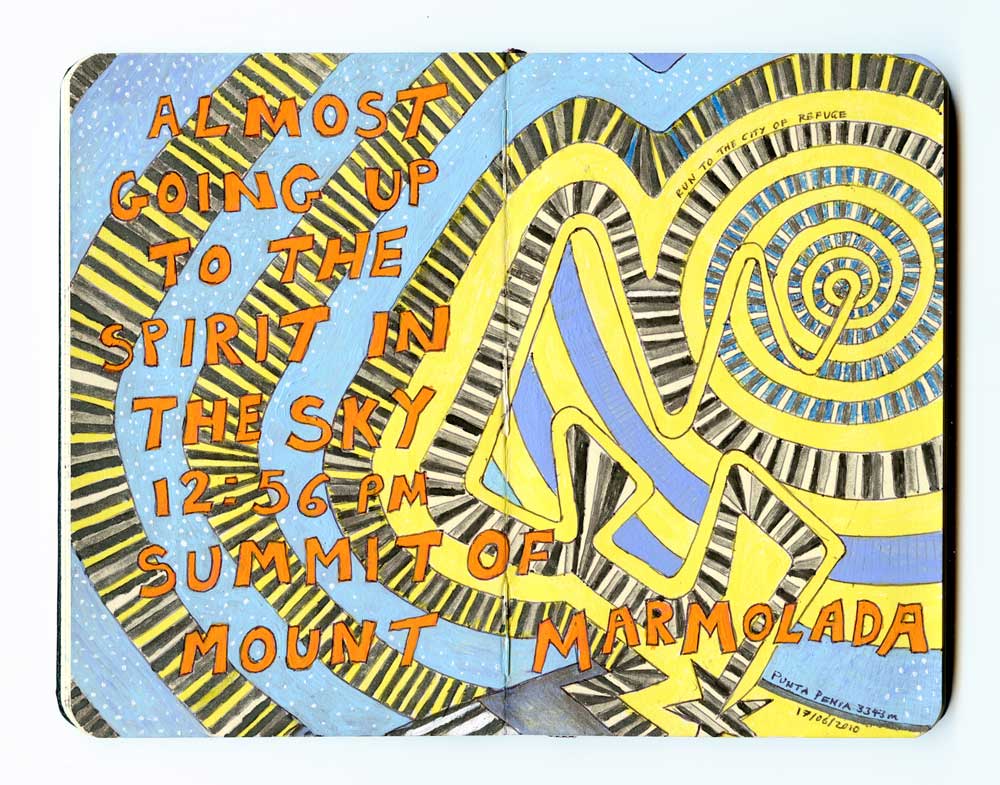

Over the last eighteen months, Shipsides and Beggs Projects have been working on an open-ended and on-going research project in the Italian Dolomites based around a type of mountaineering called via ferrata (the “iron way” developed during WW1). A small snippet of this research, involving a close encounter with lightning in June of this year on the summit of Marmolada, (the highest mountain in the Dolomites) is the basis for the work in progress presented in this show and includes ‘Every Metallic Thing is Being Beckoned’ a drawing based on the experience. It also seems appropriate with respect to the title of the Delawab show.

The Alphabet Climb, made in Montserrat, Spain during 2004 also exhibited in this show, is unrelated to the specific events on Marmolada but follows a pattern of research where climbing and mountains form the backbone of their creative act and conversation - acting as a gateway and frame to wider life, culture and society. It is typical of their dual approach where working in the moment with a focused task at hand combines with an inquisitive open-mindedness to follow chance occurrence and serendipity so that something entirely unexpected might develop - bringing new shapes and perspectives to the project.

In this vain 'The Alphabet Climb' presents a chance encounter with a young man who unaware that we are trying to make a short film about climbing a wall, interrupts, asking for information about camping. Not being camera shy, the stranger then goes on to tell the true story of his search for his missing brother Tom, after which he goes off and we go back to filming the climbing of the wall.

Since making this film we have kept in touch with Ben Moore, who by coincidence is also an artist/film maker, inviting him to work with us on a project at Be-Part in Belgium during 2008. In a similar fashion we have kept contact with Irene and John-Paul, two climbers we met on the summit of Marmolada, asking them to contribute to the work via e-mail describing their memories of the storm. These are presented in the show. (Dan Shipsides’ website info for the Death to Delawab project 18th September, 2010)

***

When power becomes gracious and descends into the visible...

(With an apology to F Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 1885, Part II, Ch 13, Those who are sublime)

The Alphabet Climb, 2004, video, installation detail. Shipsides and Beggs Projects.

The Alphabet Climb (Shipsides and Beggs Projects 2004) video collapses two actions: the climb on carved letters and chance like meeting with a man.

The accidental meeting of two narratives depends on the integrity of the artists’ intention. They risk breaking the spine of the climb/art symmetry while the story of a lost relative displaces it. Their decision to include the story, almost spontaneously, agrees with their strategies of intervention (although in the opposite direction) and of loyalty/devotion to the experience as lived. Both strategies move the video away from the ‘landscape’ towards a social interaction. The drive to link experience of climbing to some other experience operates also in the metal construction installation that runs along two flights of stairs, stops in a floor sculpture on the landing and ‘climbs out’ of the window, in a swift vertical.

Ulster Iron Way installation view, Delawab 2010.

Research image Mt. Marmolada 2010, Shipsides and Beggs Projects.

It is to recollect a mountain lightening storm experienced at the aerial conductor cone at the summit of Mt. Marmolada. Below, the drawing by Shipsides approximates the experience, even if unintentionally, it oscillates with earth cracked by earthquake or severe drought.

Every Metalic Thing is Being Beckoned. Dan Shipsides / Shipsides and Beggs Projects. 2010

The following drawing by Neal Beggs relates to the moment the lightening striked:

Mt Marmolada. Neal Beggs / Shipsides and Beggs Projects. 2010

The installation uses mostly, but not exclusively, metal, in reference to Via Ferrata (meaning “iron way”), a way accessing military strategic summits in Dolomites constructed during WW1, made of metal stemples, brackets, rungs and metal wires leading up the rock faces. The material increases the danger of electric shock during an electric storm, which in turn heightens the fragility of life, endangered immensely during the war. That allows a mental link to another storm, another conflict, a power struggle in Ulster during the early and then late 20th century.

The link between that climbing experience and regional social history is not hidden: three letters, UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force), appear in the construction/installation of the Ulster Iron Way and in the drawing of the climbing route to the top of the Marmolada summit.

The Ulster Iron Way. Shipsides and Beggs Projects, 2010.

Ulster Via Ferrata. Drawing. Dan Shipsides / Shipsides and Beggs Projects 2010.

The above works of art are parts of the collaborative Via Ferrata project (2009-2011) which proposes some equivalency between art and life. I perceive that as an intensification of a question how to insert life in art, once cherished by John Cage.

Two ideas permeate Shipsides and Beggs Projects: how “two people tied to the same rope” may insert life into art and how to transfer that experience to the disinterested viewer.

Shipsides proposes: My practice embodies a creative relationship to space and pursues experiential and participatory narrative of place. It aims to [ ] produce landscape artworks based on that experience.

Beggs emphasises the merging of art and climbing in a narrative about artist as explorer, about climber as explorer. He thought of himself as a painter who was looking for new ways of working and for greater authenticity of the result. Nature for him is something to engage with, to be stimulated through a lived experience. He went through an interesting period of preoccupation with the

idea of a perfect surface.

I hasten to add that both Shipsides and Beggs trained as painters.

The two concepts of the narrative are not that apart, moreover they morph into particular skills that both artists easily demonstrate: to pursue an experience and to produce a work of art, a surface, a landscape. The genre of landscape has an interesting Western tradition. Early on, when it replaced the golden ground in religious paintings, it favoured imagined ideal landscapes. Giotto, for example, painted leaves in the crown as if he were sitting near each of them. The emancipation of landscape received a strong paradigmatic shift in the work of so called Danube School of the 15th/16th centuries. And later on, under the care of enthusiastic Dutch painters of 17th and 18th centuries, the model of high sky above a low horizon grew in scale and complexity, hand in hand with exploration of light and clouds. Many celebrated painters joined in exploring observed world next to the imagined. Early example, almost hidden and not just under the arcade, is Baldovinetti’s fresco which includes a shepherd and mountainous landscape, not unlike the Dolomites. Acute attention to observation and sheer exuberance of conquering the mountains in the distance by the eye alone turns part of this composition into a distant predecessor of Shipsides and Beggs’ projects. Like they, Baldovinetti tolerates a chance like intervention into the intended plan, by adding a landscape as a life -narrative directly next to Nativity, a narrative of beliefs and imagination. I think of Baldovinetti’s landscape as of glorious devotion to observation similar to the poetics Shipsides mentioned above: gentle, witty and reflective.

Nativity Fresco. Baldovinetti c1462.

Nativity Fresco. Baldovinetti c1462.

Both Shipsides and Beggs use / make three-dimensional objects, work with cameras, embrace drawing, painting, sculpture and photography.

While filming Alphabet Climb the artists met by chance, a man searching for his brother. That chance acts as a metaphoric rope which seamlessly attaches his story to the intended work. Spontaneous trust that the casual and chance-like was compatible with the document of climbing and with a claim that climbing is art, accounts for healthy instinct and the force of intuition. I sense calm, almost unbearable self-confidence and simple joy of being alive and capable of making art. The lessons of cinema verite may have been forgotten, but are implicit here. The video successfully forges aesthetic unity through its relaxed tempo, fragmented glances and gentle paradoxes of disparity between an image and a sound.

In the Death to Delawab project the installation Ulster Iron Way is not a comfortable partner to this confident video. It struggles for attention, even for viewing - having part placed outside and part in a shadow. The metal rods, bound in twos (not unlike two political forces of Northern Irish “Troubles”) are almost lost at the foot of the banister. The prominent construction on landing and through a window achieve certain independence as sculptures; one becomes a strange floor sculpture, the other swishes past the window like a gothic spire, a reminder, you would recall, of the lightening storm experienced when climbing Via Ferrata on Mt. Marmolada. The metal rods and clasps of scaffolding huddle at the bottom of the banisters as an inadequate synecdoche for the gradient. Where it receives power is in an association with both effort of climbing up and meeting the trigonometric “akroterion”.

The installation is not ecstatic - it is too rational for that. Nevertheless, it veers with no warning from an eerily self-contained duo to the bursts of crazed angles and directions of the letters on the landing, through a deceptively tranquil flow through the window up and up like a wistful aria overreaching the high notes – all in a complete silence. It is more memorable than the more confident video.

Marmolada Bees, a group of framed drawings and texts displayed on the wall do not lift one’s spirit while climbing the narrow stairs in an insufficiently lit space. They demand attention to a fragmented narrative and “educational” detail.

On one hand, the artists adapted the concept to the exhibition space, in the case of the landing and the window quite wittily. On the other, the space allocated to the project was not optimal. It is a strength to tolerate inadequate conditions. Art has to negotiate hostility of all kinds most of the time.

This art practice tolerates a great deal: flexible use of means and techniques, high standards and found standards, established skills and risky abandonments.

Are Shipsides and Beggs Projects offering a new paradigm of any sort?

There are similarities shared with other art practices, like incompleteness, open-endedness and power to escape the original context while embracing its authenticity.

The similarities between climbing and Shipsides and Beggs Projects as art are not surprising or uniquely innovative.

The aesthetic categories apply to diverse human achievements, creations rooted in free will and conscious execution of aesthetics but they also apply to ordinary living. Aesthetic experience is not limited to art. All defining characteristic of art are continuous with various non-art experiences. For example, a source of direct pleasure may be music or sport. Skill and virtuosity, style, novelty, special focus, intellectual challenge, imaginative experience are all not specific to art.

The explicit courage to bind values of older art with present existence, forges a link with philosophy of becoming and with existentialism. The rock - the landscape, is in Shipsides and Beggs Projects also a means of making art away from institutionalised art world, but not in conflict with it. Yes, it escapes some theories, namely the institutional theory of art, (Dickie, G, Institutional Theory of Art), but even this does not make it a new paradigm.

Moreover, Shipsides and Beggs Projects depend on the art-world to accept them as art. But here is the first sign of innovation: both artists aim to be authentic and relevant within the climbing world. Consequently, their art rooted in two insecurities (i.e. is it art? Is it meaningful to a climber?) is willed to succeed simultaneously for two clearly defined parts of culture. This focus replaces the nebulous demands for instrumental values that have plagued art practices for far too much and for far too long. There is another aspect of accepting dual responsibilities: revival of a ‘prehistoric’ attitude to art and being. Think of the hunter/gatherer paintings at Altamira. There might suggest, is the fusion of two responsibilities, two areas become authentic in that old concept of art. I sense that the binding force is an equivalence of energy needed for living and painting.

The contemporary range of different tastes and priorities rejects this kind of focus, instead, it is the authority of an art practice that gives each culture its art system, which in turn keeps changing in relation to the available talent and constellation of conditions. Shipsides and Beggs Projects offer such a change. The negotiation of a culture (climbing) within a culture is aligned with defined skill and creativity. When something becomes art is not just a matter of agreement or analogies. The question, ‘is this art?’ is fundamentally flawed to the extent in which it aims at some correct enunciation of the nature of art, ignoring all the ongoing paradigmatic changes.

To sum up how Shipsides and Beggs Projects manage the change:

First;

their art embraces doubt as its part, uncertainty as a necessary condition, the artists experiment in vivo.

Second;

it negates the traditionalhierarchyof value / meaning production between climbing and the Fine Arts.

Third;

it values ordinary skills, knowledge, rational thought and actual testing of the process.

Fourth;

not an ideology nor a single historical context rather man’s action / experience stimulated by ‘nature’ join the imagination in inspiring a new work of art.

The paradigm shift I perceive in Shipsides and Beggs Projects consists of evocation, not an expression, narrative or depiction. The fragments of experience translate into a visual force, while applying clarity, almost precision, and simplicity. This art approximates a visual essay, a discourse through non-verbal participation - the feeling of something well done.

Its prominent characteristics appear to be unity, complexity, and intensity. Devotion, intelligence, planning ability, fitness, high skills are universal and cross cultural values capable of rousing fascination with landscape and pleasure born by the magnetic pull of mountains “When power becomes gracious and descends into visible – such descend I call beauty.” (F. Nietzsche)

The rest is ineffable.

Notes:

Nietzsche points out that for art to exist intoxication is indispensable, because art is not merely an imitation of the real but a metaphysical supplement to life:

Thus the man who is responsive to artistic stimuli reacts to the reality of dreams as does the philosopher to the reality of existence; he observes closely, and he enjoys his observation: for it is out of these images that he interprets life, out of these processes that he trains himself for life. It is not only pleasant and agreeable images that he experiences with such universal understanding: the serious, the gloomy, the sad and the profound, the sudden restraints, the mockeries of chance, fearful expectations, in short the whole 'divine comedy' of life, the Inferno included, passes before him, not only as a shadow-play—for he too lives and suffers through these scenes—and yet also not without that fleeting sense of illusion; and perhaps many, like myself, can remember calling out to themselves in encouragement, amid the perils and terrors of the dream, and with success: 'It is a dream! I want to dream on!' Just as I have often been told of people who have been able to continue one and the same dream over three and more successive nights: facts which clearly show that our innermost being, our common foundation, experiences dreams with profound pleasure and joyful necessity.

F Nietzsche, The |Birth of Tragedy, Penguin,1993,pp. 15–16

Roberta Smith, In Munster, a Sculpture Space Odyssey, The New York Times. Arta and Design, June 29 2007

Accessed on: www.nytimes.com/2007/06/29/arts/design/29muns.html?_r=1

The work is in two editions: one first exhibited at Temple Bar Gallery, Dublin and the other was published simultaneously in Source magazine. For Source magazine the images were reproduced and accompanied by an audio CD to be played while the images are viewed.

Dan Shipsides (born 1972 Lancashire, England) is based in Belfast since 1995 at Orchid Studios. He exhibits internationally including: Gecko Roof (Sporting Life, MCA, Sydney), Elastic Frontiers (Arnolfini, Bristol), Echo Valley / A Guiding Dilemma (Void Gallery, Derry) Radical Architecture (Castlefield, Manchester) and Bamboo Support (Nissan Art Project, IMMA, Dublin). His work is held within several public and private collections.

Neal Beggs (born 1959 Co. Antrim, Northern Ireland) is now based near Nantes in France. He exhibits internationally, and is represented by gallery Aliceday in Brussels. Resent solo projects include 'if muhammad' (Frac des pays de la loire, Carquefou, France), 'Lonesome in the desert', (Centre d'Art Contemporain, Château-Gontier, France), 'Children of the voyage' (gallery Elisa Plattea, Brussels) and 'Belgium is not a road', (Netwerk Art, Aalst, Belgium). His work is held within several public and private collections.

www.danshipsides.com

Alessio Baldovinetti ( 1425 – 1499), Nativity, 1460-62, Santissima Annunziata, Firenze

“ A work of art is an artefact of a kind created to be presented to an art-world public”, in Dickie, G., The Art Circle: A Theory of Art, Blackwell Publ., 1984:80

As an example par excellence I note Elastic Frontiers Shipsides made with Oldbury Primary School in Bristol, 2005-2006

Slavka Sverakova 12/01/2011